Extreme Climate Survey

Scientific news is collecting questions from readers about how to navigate our planet’s changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

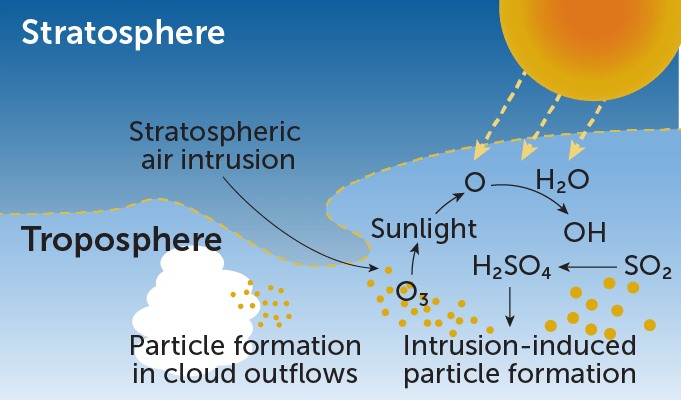

Previously, scientists have thought that most of the formation of new particles occurs in regions of the atmosphere where clouds float up into the upper troposphere and disperse. As the clouds there rain, any existing particles are washed away with the rainwater. What is left behind in these “cloud exit” regions is an empty sheet, essentially free of particles, so that the gaseous molecules have nothing on it. Instead, they create new particles.

But aerial observations suggest that stratospheric air intrusions are even more productive when it comes to particle formation. Turbulence in the atmosphere caused by the jet stream, a fast-moving stream of air, can cause fingers of stratospheric air to drop down and curl into the troposphere below.

The two atmospheric layers have very different chemical compositions, and where those air masses mix, they generate very productive particle factories, says study co-author Jian Wang, an aerosol scientist also at Washington University in St. Louis. The stratosphere is cold and rich in ozone, while the troposphere is warmer, more humid and contains a variety of molecules such as sulfur dioxide. Catalyzed by sunlight and water, the chemical reaction of these air masses can generate a variety of tiny particles, including the sulfate that seeds the cloud.

Exactly which and how many particles are being formed by these stratospheric air intrusions is a topic for future work, Wang says. “We do not understand the mechanisms in detail. We know from the data that … you need sunlight, high ozone and humidity” to produce highly reactive molecules known as OH radicals (SN: 6/4/09). These molecules eagerly interact with other gases in the atmosphere. So there are probably many different chemical reactions taking place in these regions, producing a variety of new molecules and particles.

Despite these uncertainties, the team’s analysis of the frequency and productivity of stratospheric air intrusions, compared to cloud outflow events, suggests that intrusions may be a larger source of new particles, particularly in midlatitude regions of the Earth. Earth. And climate change is expected to intensify stratospheric circulation around Earth, which in turn could increase how often the stratosphere enters the troposphere in the future. This suggests that this mechanism may become even more important for the formation of new particles, Wang says.

These findings highlight an important source of new particle formation that has long been overlooked but turns out to occur “everywhere and often” in the atmosphere, says Yuanlong Huang, an atmospheric aerosol chemist at the Eastern Institute for Advanced Studies in Ningbo. , China, which. was not included in the new study. “It’s a mechanism that’s not yet included in current models of the Earth system.”

And such a large, previously unsuspected source of new particles, in turn, could mean that the generation of these particles plays a larger role in how incoming solar radiation is distributed to Earth—including how much reaches the planet’s surface, compared to what is absorbed by aerosols and clouds high in the atmosphere – than scientists once thought.

#flow #ground #jets #helps #create #cloud #seeds

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org